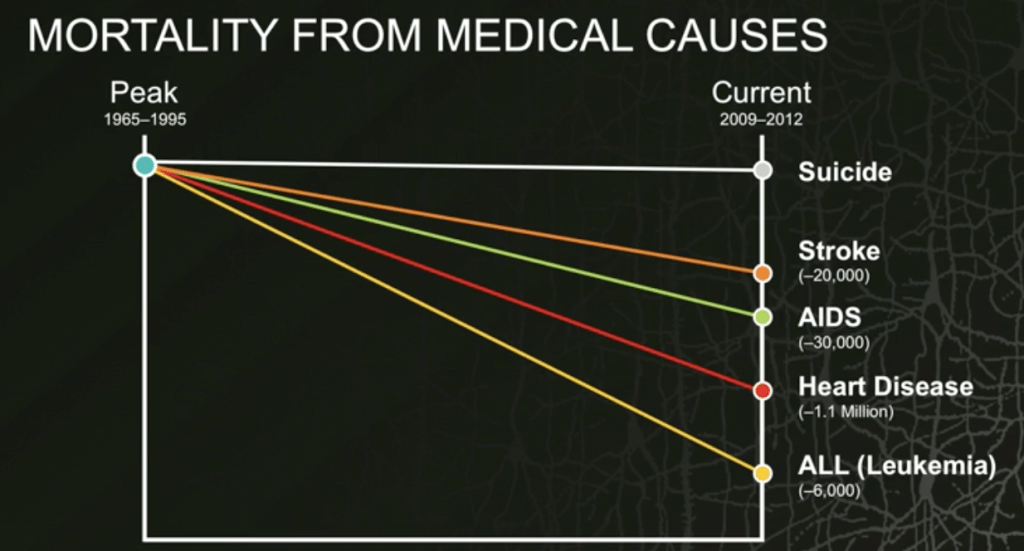

Mortality from medical causes has greatly improved over the last 50 years thanks to biomedical research (Insel, 2013). However, suicide, one of the leading events of mortality, has not improved (Insel, 2013). Thomas Insel indicates that 90% of suicides are related to a mental illness (2013). Insel mentions that early detection and early intervention is what has contributed to curbing mortality rates in leukaemia, heart disease, AIDs. and stroke (2013). Yet suicide and consequently mental illness has yet to decrease their mortality rates.

Insel discloses that mental disorders are very common, can be disabling, and that the majority of cases are early onset before the age of 24 (2013). There has been recent emphasis on mental health research from the federal and provincial levels. Large government-driven initiatives such as ACCESS Open Minds, are funding the early detection and prevention for mental health concerns in peoples under the age of 25. I am hopeful that this type of investment will help our younger generations access the mental health services they need and to be able to manage and a holistically healthy life. As Horgan indicates mental illness is easier to detect in younger generations, “because symptoms associated with mental illness do not always have the same underlying cause in older people as in younger people” (Module 4 Slide deck, 2019).

With this focus on early prevention for Gen Z and Millenials, I am left to wonder what is now left for the Baby Boomers, and those who are in their older years. Older adults face a double edge sword in this circumstance, as it is more challenging to detect mental illness and they have grown over the generations with so much stigma around mental health that it may be challenging to identify within themselves, or come to terms with such a diagnosis. Additionally, Segal, Quallls and Smyer reference that older men, generally 80 years of age or older, do not identify themselves as having depression – rather they call themselves crabby, grouchy, irritable or simply apathetic (2018, p.210). It sounds like to me that these particular research participants appear to be victims of an ageist world.

Policy is needed to help guide mental health support and services for our older adult population. Our approach to an effective model of care for mental health needs to be two pronged. One, focusing on the prevention at an earlier age, but secondly an intervention mechanism which could capture those older adults who were not apart of the prevention cohorts. Federal of provincial emphasis on health policy would ensure the holistic needs (which includes psychological, meaning mental health) of our population are being met.

References:

- ACCESS Open Minds (2019). What is access open minds? Retrieved from http://accessopenminds.ca/

- Insel, T. (2013). Toward a new understanding of mental illness. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/thomas_insel_toward_a_new_understanding_of_mental_illness?language=en&utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

- Horgan, S. (2019) Module 4 slide deck. [Powerpoint Presentation] Retrieved from https://onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/321165/viewContent/2010914/View

- Segal, D. L., Qualls, S. H, & Smyer, M.A. (2018) Aging and mental health. (3rd ed.). UK: Wiley Blackwell