main post module 3

Aging Theories and Policy

It is important to recognize how our assumptions about the older adult population have been driven by psychosocial theories. As Horgan identifies, social programs and policies, and healthcare interventions will vary tremendously, depending on which psychosocial theory of aging lens was applied to the development (2019).

As an example of how theory influences policy – this street sign on the left, which has likely been put up due to municipality bylaws, has been influenced by someone’s perception, and consequently a psychosocial theory, of aging. Why have “senior citizens” been identified as vulnerable at this intersection? Although we are missing contextual information (such as, is this right outside a senior home?) it still does imply that (1) drivers needs to be extra cautious for seniors, as seniors themselves might not be cautious and (2) seniors are out and about walking across the street.

The first point can be best supported by a biological theory of aging. Glisky indicates that older adults are slower at information processing, which can impact reaction and attention (2007) . Therefore, seniors are at an increased risk of using the cross walk incorrectly. The “Watch Children” and “Watch for Senior Citizens” signs imply that these two populations are disadvantaged in some way, perhaps cognitively, and therefore the driving population needs to drive with care.

The second point can be best supported by the psychosocial theory, activity theory, which indicates that seniors remain active and mobile in their advancing years (Wadensten, 2006), and therefore more likely to be outdoors and using crosswalks. This would contradict disengagement theory, which implies seniors withdraw from social activity and consequently would not be walking in the streets (Wadensten, 2006).

Additionally these psychosocial theories about particular populations can become dangerous for generalizations, and we need to be cognizant that individuals may not always be captured by our generalized theories.

References:

Glisky, E. L. (2007). Changes in cognitive function in human aging. Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms. In: Riddle DR, editor. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis

Horgan, S. (2019). Social theories of aging. [Online]. Retrieved from https://onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/321165/viewContent/1868375/View

Wadensten, B. (2006). An analysis of psychological theories of ageing and their relevance to practical gerontological nursing in Sweden. Journal compilation, Nordic College of Caring Science.

Connecting Theory to Practice

Access 24/7

In June 2019, a long-time coming project in the city of Edmonton finally opened it’s doors (pun intended). This collaborative care model focuses on providing 24/7 access to mental health and addictions support. The service itself is located within the Royal Alexander Hospital, which enables resource sharing which enables the integration of knowledge between the entities (the traditional hospital and Access 24/7) (Horgan, 2019). The #onedoorYEG program, also known as “Access 24/7” is run by an interdisciplinary team of medical professionals including mental health therapists, addiction counsellors, social workers and psychiatrists. Access 24/ 7 provides a range of urgent and non-urgent addiction and mental health services including service navigation, screening, assessment, referral, consultation, crisis intervention, outreach and short term stabilization.

“[People seeking mental health services] lose their voice and the ability often to advocate for what they need,” [Beaudrap] said. “Having all the resources under one roof and one door for people to go to, it’s a valuable alternative path for people to take.”

Catherine de Beaudrap, patient advocate (Edmonton Journal, 2019)

This program was designed for community-dwelling Edmontonians as a one-stop shop. The push for this initiative from Alberta Health Services and private donors indicates there is positive policy climate to begin prioritizing mental health. There is no explicit reference to working with older adults, which could be a gap in this particular model. However, this could be amended by promoting staff training in working with the unique needs of the older adult population.

References:

Edmonton Journal, Cook, D. (2019, June 17). Centralized 24-7 site for mental health services opens at Royal Alex. Retrieved from https://edmontonjournal.com/news/local-news/centralized-24-7-site-for-mental-health-support-opens-at-royal-alex

Horgan, S. (2019). Collaborative (integrated) mental health care. [Online]. Retrieved from https://onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/321165/viewContent/1868389/View

Caregiving & Respite Services

Informal caregiving is a hugely underrated resource, as this contributes billions of dollars in unpaid labour to the Canada Health System (Hajek & Konig, 2015). The consequences of failing to provide respite can include caregiver burnout, crisis, neglect, and abuse (Health Canada, 2003). Health Canada goes on to report that some of the largest groups requiring respite services are elderly spouses or elderly patients, and middle-aged children who are taking care of their own children and their aging parents (2003). The coverage for such services varies between provinces as respite services fall under health jurisdiction. Health Canada reports that in Newfoundland and Labrador, “mental health clients are only eligible for general home care programs [(which provide indirect respite)] if they also have a physical disability or illness (2003).” Although this statement is over 15 years old, it’s shocking to see that this was ever the case. Based on my preliminary review, it appears British Columbia, Ontario, and Yukon, offer explicit mental health respite services. I could not find any information about respite services for Mental Health explicitly, in Alberta.

Provincial policy across the country can improve by incorporating mental health clients in their eligibility criterion for respite services. Specialized services could also be developed, such as respite care for older adults, adults, and children as their needs may differ.

References:

Hajek, A. & Konig, H. (2016). The effect of intra-and intergenerational caregiving on subjective well-being- evidence of a population based longitudinal study among older adults in Germany. PLOS ONE,DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0148916

Dunbrack, J., Health Canada (2003). Respite for family caregivers – An environmental scan of publicly-funded programs in canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/reports-publications/home-continuing-care/respite-family-caregivers-environmental-scan-publicly-funded-programs-canada.html

Stigma

Stigma is experienced when a person or group of individuals have a particular characteristic (ie. a chronologic age), and there is a negative attitudinal association with such characteristic. Older adults with mental health issues are doubley stigmatized as being “old” and having “mental health issues.”

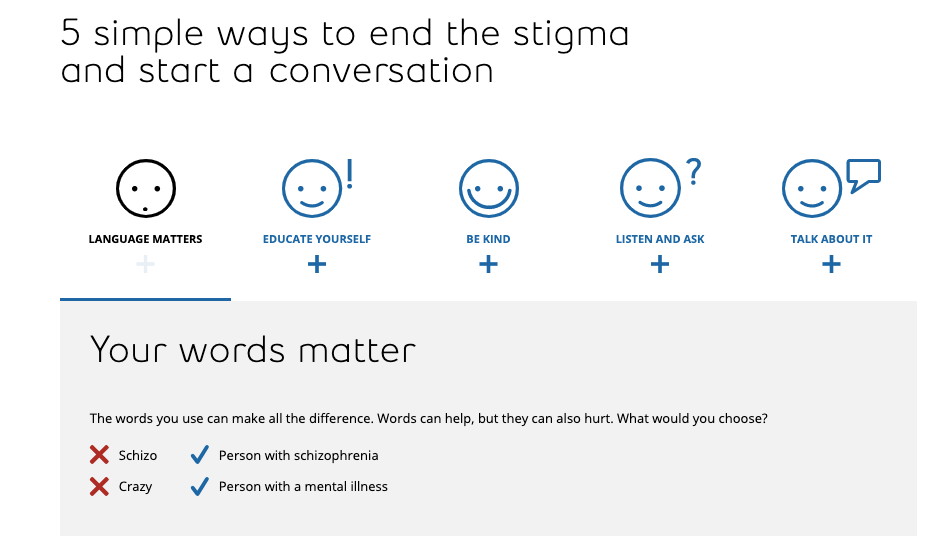

Stigma can be very simply understood as a fact about a person, which is being perceived by others in a particular way (which is typically negative). We cannot change these facts; whether someone is 65 or if someone has clinical depression – but we can change our attitude towards these facts. What’s sad about stigma, is it really has more to do with others than it does with the individual presenting the characteristic. Mental health policy, from a governing level (federal or provincial) could greatly influence educational programs to raise awareness and to help combat stigmatization towards mental health and ageisim. Some private companies have already done great work to start these conversations, despite the lack of governing mental health policy. Most notably, Bell Let’s Talk.

Click on this link to use the interactive tool Bell has made!

Aging in Place

“Aging in Place” is a similar, but different idea from universal design. This approach focuses on removing barriers, keeping the 7 principles of universal design in mind, but with the ultimate goal of having older adults stay in their homes for as long as possible. Aging in Place also encompasses more holistic features to remain in the home, such as considering arrangements for personal care, household chores, meals, etc. However there is an emphasis within this to adapt the design of your housing to make it “easier and safer” to live in (National Institute on Aging, 2017). This would include adding a ramp at the front door, grab bars in the bathroom, nonskid floors or altering the handles on doors and faucets.

Some local municipalities offer funding programs to help support civilians in making these adaptions to their home and to further age in place. This type of funding program would have required policy to guide the direction of this.

References:

National Institute on Aging (2017). Aging in place: Growing older at home. Retrieved from https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/aging-place-growing-older-home

Universal Design Policy

Public organizations such as municipal governments, or colleges and universities can be guided by policy to enact universal design in their building codes. Some examples of Universal Design Policy have been found below:

- City of Winnipeg: https://winnipeg.ca/ppd/planning/pdf_folder/EPC_UnivDesign.pdf

- Red Deer College: https://rdc.ab.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/43160/universal-design-policy.pdf

Private institutions, such as shopping malls or restaurants, are not at the discretion of this public policy, and will need to come to terms with generating universal design in their own means. I can see this as problematic as not all buildings which the public interacts with (private or public) will be fully accessible. I hypothesize that an inaccessible design could lead older adults to remain isolated from venturing out of their homes due to fear. The lack of universal design may be contributing to a worsened state of mental health, which is reason enough for all private and public institutions to adopt universal design policy.

The Butterfly Project

This initiative designed by Dementia Care Matters first began in the United Kingdom. Over the last 20 years, this approach to care has sparked interest in Ireland, Australia, the USA and Canada. The first commissioned pilot project, from Dementia Care Matters occurred in two towns in Alberta – Spruce Grove and Whitemud (Sainsbury & Gaudet, 2018). The Butterfly project promotes an organizational culture shift – staff are taught that “feelings matter most” and that there is meaning behind every behaviour of resident’s. More about this initiative can be learned by watching the video below!

What I enjoy most about watching this video, is seeing the mutual joy among residents and staff. I also appreciate how this model encourages residents to be embraced with touch (ie. hugging). This type of project requires a change in organizational/institutional values, which in turn can feed into the policies that are set by the organization. As an example, an institution would need to create a policy that outlines all new staff must complete staff training that reviews dementia care (as per the Butterfly Model).

At 4:39 the video indicates that some of the benefits of this human-centred initiative include (1) reduced antipsychotic drugs and (2) reduced cases of worsened depression. As this method emphasizes staff working with residents’ feelings, it appears there could be a connection between emotions, mental health, and these documented results.

There is growing popularity and uptake in there projects across the country, it would be wonderful to see this type of model be embraced among all long-term-care facilities!

References:

Sainsbury, R.K. & Gaudet, N. (2018). Lifestyle options/choices in community living ‘life my way. Living well with dementia’ Final report. Retrieved from https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/about/scn/ahs-scn-srs-cig-life-my-way-2018-final-report.pdf

Smart Homes

Smart homes, duped up in Alexas, smart light bulbs, thermometers, and cameras, seem to be the wave of the future. These home modifications fall within the umbrella term of assistive technology, which includes technology that is assistive, adaptive, or rehabilitative for people with disabilities (Horgan, 2019). As an example, a person who uses a wheelchair would be able to adjust the heat of the thermostat by using their mobile device (rather than attempting to reach for the thermostat which is relatively high on the wall). People with disabilities, including mental illness, could also benefit on using the video conference calling features to speak with loved ones and maintain their connections outside the home (if mobility issues exist). Alternatively, community dwelling seniors could be connected with an online therapist via video conference calling , or telephone. Some new businesses that support this digital counselling model include Talk Space and Better Help.

Although I think there is immense potential for Smart Homes to improve the lives of older adults, and those people with disabilities such as mental illnesses of physical impairments, there are a select few subgroups which I am wary about. The first being, people with schizophrenia. A common paranoia is that a third party, aliens, other people, etc. were “watching” the person, or telling them what to do (Living with Schizophrenia, 2019; Saks, 2012). With so many responsive and interactive artificial intelligence devices, I’m concerned that this could be a triggering environment. Secondly, the installation of these devices is not always user-friendly which is not ideal for the older adult population. It would be ideal to have assistance with installation, but also brief, in-person training on the product to ensure it is used with confidence.

References:

Horgan, S. (2019). Special topic. Assistive technologies. [Online Module] Retrieved from https://onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/321165/viewContent/1868393/View

Living with Schizophrenia. (2019, May 13). What a psychiatric hospital is like. [Video file] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Mww7mFqyVA

Saks, E. (2012). A tale of mental illness – From the inside. [Video file] Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/elyn_saks_seeing_mental_illness?language=en&utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare#t-468177