I was able to come across several policy related documents for the province of Alberta, but the documents seem to be outdated with one being more than 15 years old. The only document below to make explicit reference to geriatric mental health was “Aging Population Policy Framework.” There were no benchmarks listed in this document, which makes it challenging for accountability to be had.

- Aging Population Policy Framework (2010)

- “provide leadership and support for initiatives which enhance knowledge about the mental health needs of seniors, and partner with key stakeholders and service providers to develop innovate responses to these needs.” (p. 28)

- “support rural Albertans in accessing health services, including those related to mental health, and facilities that support complex care.” (p.29)

The government of Ontario appears to have the following geriatric policy related documents:

My critique of this Ontario document again is that it lacks benchmarks – how do we know what measures success? The action plan indicates three areas of focus (1) support seniors at all stages, (2) supporting seniors living independently in the community and (3) seniors requiring enhanced supports at home and in their communities and (4) seniors requiring intensive supports.

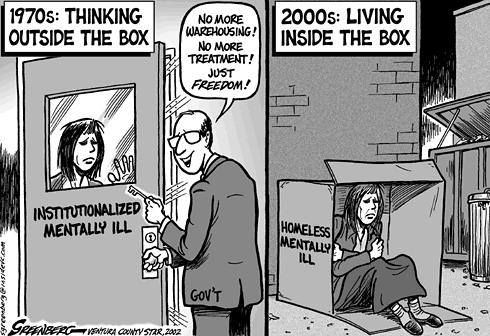

Undergoing this preliminary search lead me to reflect more on who’s responsibility is it to create mental health policy for seniors? Our provincial government can have a new party in power every 4 months, it seems both necessary yet unsustainable for these policy action plans to be recreated every few years. Additionally, another observation I made was that there is no standardization as to what types of documents are being produced from the province. Ontario makes an “Action Plan” and Alberta creates a “Policy Framework” and “Strategic Framework.” This, adding to the challenge of comparing the two provinces objectively.

While undergoing my search for related policy documents coming from the provincial level, I stumbled across other jurisdictions. This included the Canadian Medical Association, Association of Municipalities Ontario, Regional Geriatric Program of Toronto. Can these third party agencies take responsability in shaping mental health policy for seniors? This would support Horgan’s point that “policies be informed by older adults who experience mental health issues to ensure that they adequately meet their needs and are in-line with their values (2019)”

References:

Horgan, S. (2019) Mental health policy for older adults. [Online]. Retrieved from https://onq.queensu.ca/d2l/le/content/321165/viewContent/1868392/View